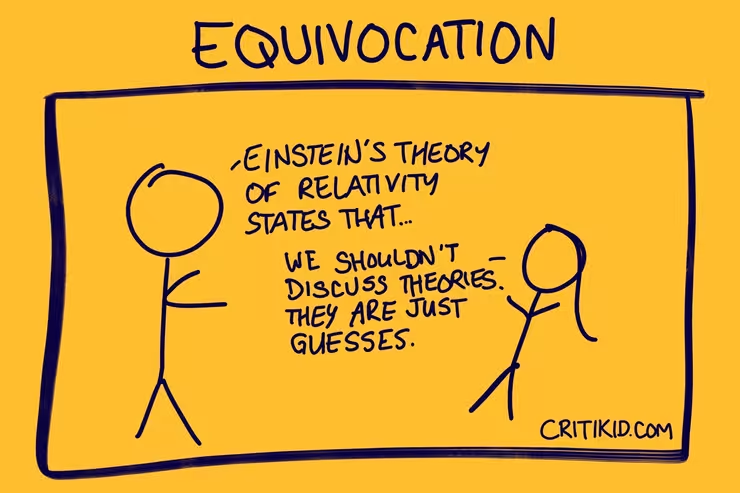

Equivocation

“Nothing is better than a good night’s sleep. A slice of pizza is better than nothing. Therefore, pizza is better than sleep.”

This joke works because “nothing” is used in two different ways. When someone uses a word with more than one meaning inconsistently to make a point or win an argument, this is a logical fallacy called equivocation.

For example: “Plate tectonics is just a theory. I have my own theories.” In science, a theory is a well-supported explanation that organizes evidence and makes predictions. In everyday talk, “theory” means “hunch”. Plate tectonics is a theory in the scientific sense; by implying it’s equivalent to their own “theories” (i.e., hunches), the speaker mixes up the meanings.

As a real-world example, Colgate once advertised “80% of dentists recommend Colgate.” They knew that most people would hear “recommend” as “prefer above all.” The survey, however, asked whether dentists would recommend Colgate among several acceptable brands. “Recommend” meant “select as an option,” not “select as the best option.” When we realize this, the fact that only 80% of dentists recommended Colgate is surprisingly low.

Equivocation can happen with whole claims too. This is called the motte-and-bailey fallacy. You commit the motte-and-bailey fallacy when you make a bold, hard-to-defend claim, then—when challenged—retreat to a weaker, easier claim, defend that one, and act as if you’ve defended the original. For example:

A: “Homeopathy cures many illnesses.”

B: “There’s no evidence beyond placebo.”

A: “But placebo makes people feel better.”

The second claim that A made is easy to defend, unlike the first one. If A defends the second claim and then acts as if they have defended the first one, they have committed the motte-and-bailey fallacy.

Buy a printable version of this handbook.

Teach your kids about logical fallacies with Critikid's Fallacy Detectors.